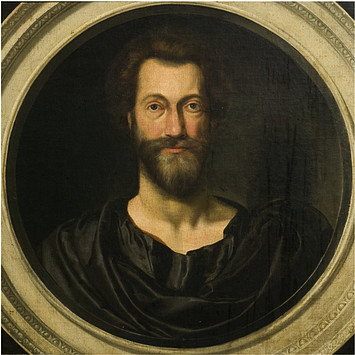

Oil Painting, John Donne (1573-1631), at the age of 49. Anon. British School, 1622. Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

JOHN DONNE IN 1622

In the fall of 1622, John Donne, at the age of 49, had been Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral for just over a year. He owed his position at St Paul’s to James I. The King had promised Donne that if he would agree to ordination to the priesthood in the Church of England, the King would guarantee Donne a significant position in the Church.

When Donne was ordained, in 1615, the King secured Donne a Doctor of Divinity degree from Cambridge University and named Donne a Royal Chaplain, amid rumors that he intended to have Donne appointed Dean of Canterbury Cathedral. This did not happen, however, and Donne went on to other jobs in the Church of England, most especially serving as Reader in Divinity at Lincoln’s Inn from 1616 until his appointment, at the King’s request, as Dean of St Paul’s in 1621.

By 1622, Donne had become an experienced preacher of the one- and two-hour sermons expected of clergy in the seventeenth century. Because of Donne’s close connections with James I, it was appropriate that Donne be called on by the King to preach sermons in defense of or apologizing for the King’s policies in religious affairs and, therefore, indirectly, political affairs as well. .

Donne preached two sermons at Paul’s Cross in the fall of 1622 at James’ request, the second of which is the one at the center of the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project. The first, Donne’s sermon for September 15th, 1622, is worthy of mention because it sets the stage for Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon, delivered November 5th, 1622.

The broader political context for both these sermons is the desire, on James‘ part, to secure a political alliance with the Spanish, as well as a substantial dowry to augment the Royal Treasury, by arranging the “Spanish Match,” a marriage for his son Charles with the Spanish princess Maria Anna, the youngest daughter of King Philip III of Spain and Margaret of Austria.

By 1622, efforts to secure this marriage had been going on for some 8 years, with the religious implications of a potential marriage between a Protestant groom and a Catholic bride begin among the major points of contention in the negotiations. The possibility of England’s becoming Catholic again, or even of Catholic worship being permitted openly in England again, raised fears — and anti-Catholic sentiments — among many Englishfolk, especially among Puritan clergy and their supporters.

In response to active public opposition, let by the Puritan party in the Church of England, James issued in August of 1622 a document called Directions for Preachers that sought to limit the range of subject matter and approach in sermons.

Clergy were ordered to advocate no position that was not “comprehended and warranted, in essence, substance, effect or natural inference, within some one of the Articles of Religion . . ., or in some of the homilies set forth by authority of Church of England . . . as a pattern and boundary . . . for the preaching ministers.”

Further, “no preacher of what title soever under the degree of bishop or dean . . . do from henceforth presume to preach in popular auditory the deep points of predestination, election, reprobation, or of the universality, efficacy, resistibility or irrestibility, of Grace; but leave those themes rather to be handled by the learned Drs and that moderately and modestly.”

Also, no preacher “shall presume . . . to declare, limit, or bound out, by way of positive doctrine, in any lecture or sermon the power, prerogative, and jurisdiction, authority, or domain of sovereign princes, or otherwise meddle with these matters of … and the differences betwixt princes and the people.”

Further, “no preacher . . . shall presume . . . to fall into bitter invectives and indecent railing speeches against the person either Papists or Puritans, but modestly and gravely (when they occasioned thereunto by the text of Scripture), free both the doctrine and discipline of the Church of England from the aspersions of [any] adversary.”

Finally, only clergy licensed by the Bishop of the Diocese (“which his Majesty hath good cause to blame for their former remissness” and who should grant such a license carefully and warily and “under his hand and seal,” with the permission of “the lord archbishop of Canterbury, and a confirmation under the Great Seal of England”) should be permitted to preach.

The apparent balance in this document between parties, limiting “invectives and indecent railing speeches against the persons of [both} Papists and Puritans,” only aroused further anxieties about the religious allegiances of King James and the potential threat of a national conversion to Catholicism.

James called upon Donne to defend the Directions for Preachers in his Paul’s Cross sermon of September 15, 1622. Here, in addition to affirming the benefit of James’ imposition of limits on preaching, Donne reminds his auditors that the subject here is really one of royal authority, that subjects are called upon to obey their monarchs, and that obedience includes trust in their wisdom, hence subjects should trust James’ stated reasons for issuing the Directions rather than connect them to the negotiations for the Spanish Match.

Gunpowder Day in 1622 offered the crown yet another opportunity to reassure the populace about the King’s religious allegiances as well as to reassert the royal prerogative in religious as well as political affairs. After all, James was the person whom Catholic plotters intended to kill, above all others, in the original Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

In this second public effort to shore up support for James in the fall of 1622, Donne insists that good subjects owe their trust and obedience to the monarch regardless of whether he is a good king (Josiah) or a bad king (Zedekiah). The fault of Catholics is precisely in their disobedience, in their refusal to “have this man to reign over us” (Luke 19:14). Nevertheless, Donne is also quick to defend James as a Josiah, a “good king,” echoing the rhetoric of the reign of Edward VI when Edward in his efforts to transform the Church of England from a Latin to an English church was leading a reformation like the one Josiah led. Donne also reassures his congregation that James is a “good text man,” and no “good text man” would ever be a Papist.

James’ interest in what Donne said on Gunpowder Day in 1622 led to his asking Donne to send him a copy, the copy that eventually became MS Royal. 17.B. XX, and the basis for the script we are suing in this situated simulation of Donne’s sermon for November 5th, 1622.

The portrait of Donne shown above is in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. A copy of this painting hangs in the study of the official residence of the Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral in London. This portrait dates from the early 1620’s and shows Donne at about the age of 49.