Figure1: Paul’s Cross, from 75 feet. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

THE SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT

Paul’s Cross sermons may well be regarded as occasions for establishing a religious presence within a larger public sphere. The wall of buildings around Paul’s Churchyard must have created a sense of separation for this space from the rest of London, a sense of enclosure that made this space a world apart from the busy world of urban London in the 17th century, perhaps quieter, perhaps less hectic.

Paul’s Churchyard was home to a large number of people, as evidenced by the presence of two parish churches — St Gregory’s and St Faith’s — inside the boundaries of Paul’s Churchyard. These folks included not only the Dean and the cathedral staff, but also the Bishop of London and his staff, the staff and students of St Paul’s School, and a long list of other people related in some way to the work of the cathedral, the Diocese of London, and the booksellers’ shops that surrounded the Cross Yard.

Figure 2: Detail, John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

The primary work of St Paul’s Cathedral was the maintenance of regular worship in the cathedral’s Choir according to the cathedral style, that is, the observation of the Daily Offices of Morning and Evening Prayer, with the use of organ music and the singing of canticles, anthems, and Psalms by the choir of men and boys, together with observations of the appropriate additional services of the Great Litany and Holy Communion on Sundays, Fridays, and Holy Days in a similar style.

Music written for the St Paul’s organ and the Cathedral’s Choir in this period by musicians associated with the cathedral like Adrian Batten and Orlando Gibbons and preserved in manuscripts at St Michael’s College in Tewksbury and the Royal Academy of Music in London, remind us that this period constitutes the beginning of the great English Choral Tradition that still flourishes today.

This work was conducted in the cathedral’s Choir, a relatively small part of St Paul’s vast bulk, a space about 100 feet long and 30 feet wide, seating fewer than 150 people. When Christopher Wren designed the current St Paul’s Cathedral after the Great Fire, he planned for seating on the Choir for about 120 people, a good guide to the seating capacity for that part of the building he was replacing.

The regular conduct of worship according to this style creates within a larger urban world an oasis of calm that can be exceptionally powerful. John Milton, who attended St Paul’s School from 1620 to 1625, described the experience of attending such worship in his poem “Il Penseroso”:

. . . let my due feet never fail,

To walk the studious Cloysters pale,

And love the high embowed Roof,

With antick Pillars massy proof,

And storied Windows richly dight,

Casting a dimm religious light.

There let the pealing Organ blow,

To the full voic’d Quire below,

In Service high, and Anthems cleer,

As may with sweetnes, through mine ear,

Dissolve me into extasies,

And bring all Heav’n before mine eyes.

Nevertheless, for a variety of reasons, there seems to have been constant interaction between this space and the larger world of urban London around it. The location of the cathedral — occupying a significant space in a busy part of London — meant that there must have been significant numbers of people who had to pass through this space to get to someplace else in London. The large enclosed space created by the cathedral’s nave and the commercial space for booksellers in the Cross Yard gave them reason to stop.

The sermons at Paul’s Cross seem to be, in great measure, an effort by religious authorities, especially the Bishop of London, to engage the public space around St Paul’s in religious conversation. The construction of the Paul’s Cross preaching station by Bishop of London Thomas Kempe in the later 15th century parallels the growing use of St Paul’s nave as a space for gathering, selling, and marketing.

Francis Osborne gives us the flavor of Paul’s Walk as a social space: “the principal gentry, lords, courtiers, and men of all professions not merely mechanic . . . meet in Paul’s Church by eleven and walk in the middle aisle till twelve, and after dinner from three to six, during which times some discoursed on business, others of news.”

People complained about the noise from Paul’s Walk interfering with worship in the Choir. but no one shut the doors, or otherwise stopped Paul’s Walk’s growing reputation as “the great exchange of all discourse, and no business whatsoever but is here stirring and a-foot” where the “noise in it is like that of bees, a strange humming or buzz mixed of walking tongues and feet: it is a kind of still roar or loud whisper.” (William Haughton)

The relationship between secular and religious activities in this place continued throughout the early modern period, as the Reformation encouraged the development of the English book trade. People drawn to the Cross Yard for a Paul’s Cross sermon might have returned to buy a printed copy of that sermon, or a Book of Common Prayer, or any of the other books on offer in the shops that by the beginning of the 17th century ringed the Cross Yard and covered the east side of the north transept.

The Congregation

Donne, in the prayer which which he begins his Gunpowder Day sermon for November 5th, 1622, describes the congregation gathered before him as comprising a microcosm of London’s population, “a great Congregation of thy Children . . . of all sorts . . . from the Lieutenant of thy Lieutenant, to the meanest sonne of thy sonne,” now “come” together in this “Assembly, . . . with hearts, and lippes, full of thankesgiving.”

Mary Morrissey, who knows more than anyone about the Paul’s Cross sermon, has suggested to me that in this passage “the Lieutenant of thy Lieutenant” is the Lord Mayor of London, who in November of 1622 would have been Sir Edward Barkham, an English merchant who was a member of the Worshipful Company of Leathersellers. He had served as Sheriff of London from 1611-1612. He was knighted in June of 1622.

Paul’s Cross sermons were significant social occasions for the Lord Mayor of London and his entourage. They would have occupied the seats of honor in the Sermon House in the absence of royalty or members of the Court. Their presence is a reminder that these sermons were targeted primarily at citizens of London and visitors to the city.

How far down on the social scale one has to go to reach “the meanest sonne of thy sonne” is another matter. Gunpowder Day was a holiday in early modern England, so theoretically anyone could come to them. On the other hand, the comment by Osborne, above, about how those who frequented Paul’s Walk did not include those whose profession was “merely mechanic,” is a reminder that in a hierarchic society there are always those at the lower end of the social scale who do not exist except as help to their social betters.

The size of the crowd, on the other hand, is of direct concern to this project. Sixteenth-century estimates of crowd sizes at Paul’s Cross sermons range as high as 5,000 to 6, 000 people. Morrissey suggests, however, that the size of these crowds shrank during the 17th century. It is also the case that contemporary images of the Paul’s Cross sermon never show more than 250 people in attendance.

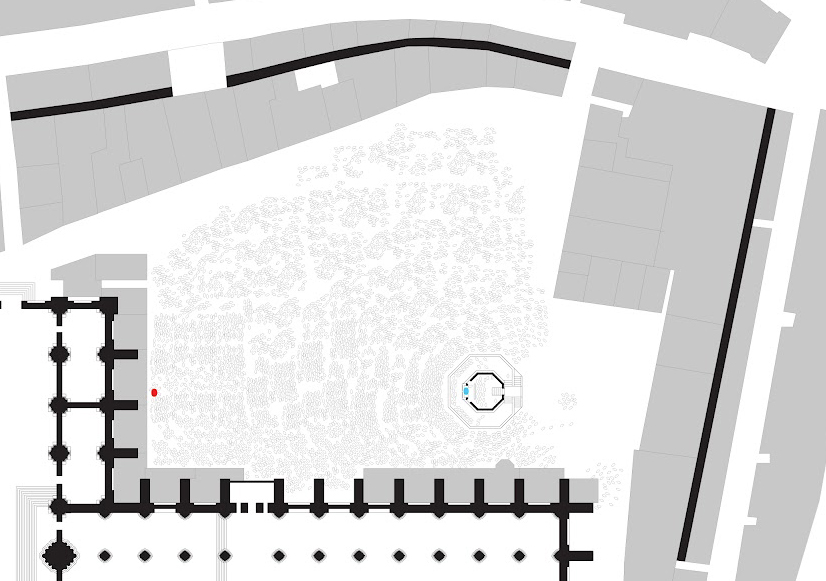

Nevertheless, it would be possible for crowds in the thousands to be able to see and hear Donne preaching this sermon. Based on the notion that someone needs 4-5 square feet of space to occupy comfortably, here is how a crowd of about 5, 000 would fit into the Cross Yard:

Figure 4: Paul’s Churchyard with 5000 people. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens.

This is how Paul’s Cross would appear to someone standing at the back of a crowd of this size.

Figure 5: Paul’s Cross. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

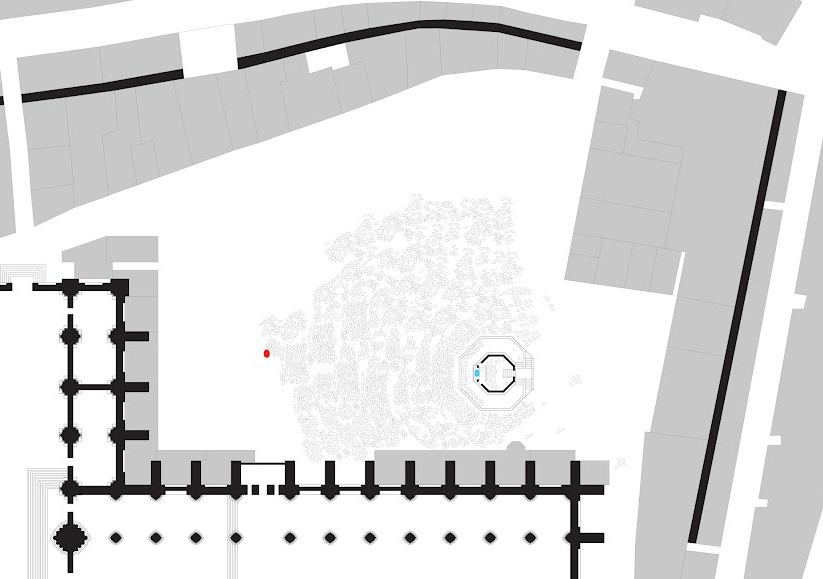

Here is how a crowd of 2, 500 people would fit:

Figure 4: Paul’s Churchyard with 2500 people. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens.

Here is how Paul’s Cross would appear from the perspective of someone standing at the back of a crowd of this size.

Figure 6: Paul’s Cross. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

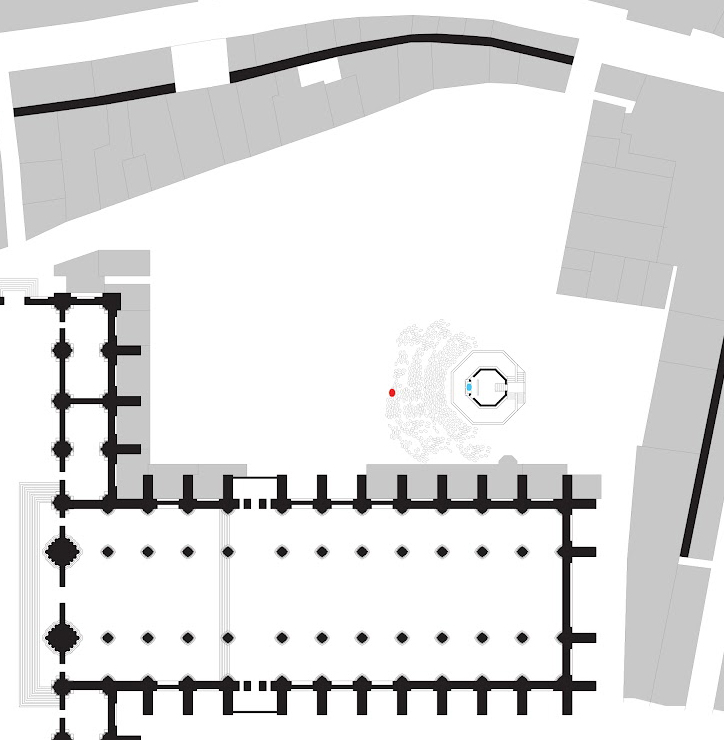

Here is how a crowd of 500 people would fit into this space.

Figure 4: Paul’s Churchyard with 500 people. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens.

And here is how Paul’s Cross would appear to someone standing at the back of a crowd of that size.

Figure 7: Paul’s Cross. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

Go to the INTERACTION page to experience how crowds gathered at Paul’s Cross might have interacted with the preacher.