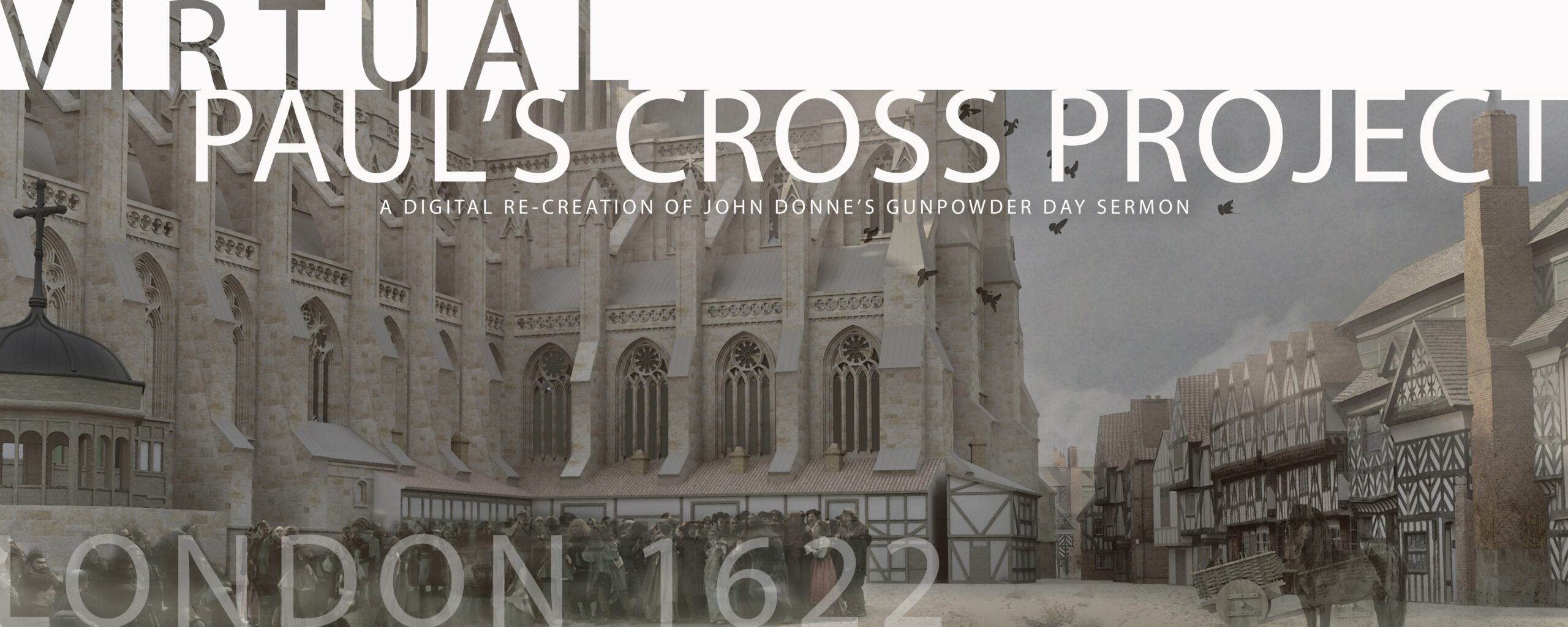

Figure 1: Paul’s Cross from 15 feet, from the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

STAGING THE PAUL’S CROSS SERMON

Part of staging any public event is the task of identifying the events that need to take place, the names of the participants, and the order in which the events will proceed. This is true even when the event is basically a straightforward one, like the Paul’s Cross sermon, with its one chief actor, one main set, one basic arrangement of participants, and one time frame.

Figure 2: John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

We know some things about the conduct of these events. We know, for example, that the preacher had with him in the preaching station refreshments, perhaps some wine and bread, to fortify him during the course of his preaching. We know that he had an hour glass to mark the time of the sermon, and that he began by declaring the text and turning that glass before he set out on the course of his preaching. Gipkin shows us a preacher wearing standard clerical vestments for formal occasions, that is, a black gown, a white ruff, a white surplice, a black cap, and a black scarf, known as a tippet.

Figure 3: Detail from John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

Nevertheless, much about the conduct of events for these occasions remains a mystery. Neither of the surviving texts of Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon for November 5th, 1622 tells us, for example, where in the cathedral he donned his vestments or how he proceeded from there to the preaching station, or how, once he arrived and entered the pulpit, he gathered the crowd’s attention and declared that the event was beginning. Nor are we told whether anything, either verbally or in terms of physical movement, proceeded or followed the sermon itself.

There are clues, however, and Gipkin supplies one of them. In his painting of a Paul’s Cross sermon, standing behind the Cross itself is this figure.

Figure 4: Detail from John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

If we ignore the horses’s hoof intruding into this image and making it look like the man in the image is carrying a torch, we can recognize this figure as the cathedral’s Verger, carrying his “virge,” or wand, his symbol of office. The Verger was the “Protector of the Procession”; his role was to lead processions of clergy and their attendants from the Vestry (vesting room) to the place of worship or assembly, using his virge to clear the way through crowds of people and animals.

This Verger’s presence is a sign that the occasion of a Paul’s Cross sermon began with a formal procession from the cathedral to the Cross itself, led by the Verger and perhaps other attendants who preceded the preacher.

If, as David Crankshaw suggests, clergy vested at St Paul’s in John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster’s Chapel, an old chantry chapel on the north side of the Choir, (St Paul’s, 53), then probably the procession exited the cathedral through one of the doors shown in Hollar’s drawing of the north side of the Choir and made its way across the Cross Yard to Paul’s Cross.

Figure 5: Detail, Wenseslaus Hollar, drawing, St Paul’s Cathedral, north side (1650?). Image courtesy Image courtesy Image courtesy of Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Donne was the Dean of St Paul’s, a dignitary worthy of an entourage in processions, so perhaps the people shown by Gipkin as sitting inside the Cross itself are people who were part of that formal procession and this is where they would have ended up after reaching the Cross. Perhaps, in fact, this figure, shown by Gipkin as sitting on the wall in front of the Cross rather on one of the benches or chairs and looking out over the crowd rather than back at the preacher is also a member of the procession.

Figure 6: Detail from John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

In Gipkin’s painting, all these folks are standing by, waiting for their time to come around again, forming a recessional to convey the preacher of the day back to the cathedral, and to the vesting room for disrobing, and to lunch.

Having gotten the preacher to the Cross, we imagine him gathering himself and moving into the pulpit, to stand before the gathered congregation. He must get their attention, must focus their attention on himself. How did he do that?

The Book of Common Prayer supplies an answer, the traditional exchange of versicle and response before prayer — “the Lord be with you/ And with thy Spirit.” But is its use here justified?

Language used in the prayer that begins Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon locates this sermon in a liturgical context. Donne asks, “O Lord open thou our lips, and my mouth shall shew forth thy praise; for thou, O Lord, didst make haste to help us.”

Donne’s congregation would have recognized instantly this allusion to the versicles and responses of the Book of Common Prayer’s Office of Morning Prayer, as well as other rites:

Prieste. O Lord, open thou our lippes.

Aunswere. And our mouthe shall shewe furth thy prayse.

Prieste. O God, make spede to save us.

Aunswere. Lord, make haste to helpe us.

A few lines later, Donne evokes the texts of Morning Prayer again, with the lines “We praise thee, O God, we knowledge thee, to bee the Lord; All our Earth doth worship thee” echoing the opening lies of Te Deum, one of the Canticles for Morning Prayer: “We prayse the, O God, we knoweledge the to be the Lorde/ All the earth doth worship the, the Father everlastynge.”

Soon he echoes yet again the lines we noted before: “Thou Lord openest their lippes, that their mouth may shew forth thy prayse, for, Thou, O Lord, diddest make haste to helpe them, Thou diddest make speede to save them.”

Donne’s congregation would, presumably, have come to Paul’s Churchyard from local parish churches, or from the Choir of St Paul’s, where daily Morning Prayer would have been said or sung. Donne’s verbal echoes of this rite link the extra-liturgical occasion of the Paul’s Cross sermon to the liturgical practices of the Church of England.

For this reason, we have borrowed from the Book of Common Prayer necessary texts to enable this Paul’s Cross sermon to be performed. A gathering of hundreds, if not thousands, of people needs a Call to Order; we have supplied, from the Prayer Book, the definitive Call to Order for people formed as Christian people by use of the Prayer Book, that is “The Lord be with you/And with thy Spirit./Let us pray.”

In like manner a text must be introduced, so we have the actor performing Donne’s sermon using the form for introducing a reading from the Bible, again taken from the Prayer Book, where it is used to announce readings at the Daily Offices of Morning and Evening Prayer and also at Holy Communion.

So, the preacher has been escorted to the Cross, has attracted the attention of the crowd, has delivered his sermon, and is now ready to leave. The Verger and the rest of his processional party await, to escort him back to the cathedral. How do they leave?

According to some contemporary accounts, the sermons at Paul’s Cross ended with another liturgical element, the singing of Psalms. In fact, in the Gipkin painting of a Paul’s Cross sermon shows the Choir of St Paul’s perched upon a balcony of the cathedral waiting the opportunity to lead the congregation in singing.

Figure 6: Detail from John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

Psalm-singing was part of worship in cathedrals and parish churches. The Book of Common Prayer organizes readings from the Psalter daily at Morning and Evening Prayer of sufficient length that the Psalter is gone through completely every 30 days.

Two traditions for Psalm-singing then were practiced in England. One was the developing tradition of Anglican Chant, a 16th century outgrowth of the medieval plainsong tradition that made it possible to chant the Psalms in the Great Bible translation preserved in the use of the Church of England until recently.

The other was the tradition of rewriting the Psalms in meter and singing them to familiar tunes. This tradition dates from the middle of the 16th century and is associated especially with the names of Sternhold and Hopkins, whose collection of 34 metrical Psalms was published in 1549, the year of publication of the first Book of Common Prayer.

This collection was gradually expanded to incorporate all 150 Psalms, and was published in 1562 by John Day under the title The Whole Booke of Psalmes, Collected into English Meter . Day’s edition also included metrical settings of the Creeds and the Canticles of Morning and Evening Prayer, which made it possible for there to be sung services of the Daily Offices in even the most humble of parish churches.

This tradition flourished in England, with over 200 editions of the metrical Pslater printed between 1550 and 1640. One notable edition, published in 1621 — the year before Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon — by Thomas Ravenscroft, added many more psalm tunes by such notable composers of the day as Thomas Morley, organist at St Paul’s in the late 1500’s;Thomas Tallis, and Thomas Tomkins.

One would like to think that the Psalms sung at the end of a Paul’s Cross sermon would be sung to the tunes, and in the metrical versions, of the Sternhold and Hopkins tradition, since they represented the parish tradition of sung worship in the early modern period, ans since the Paul’s Cross sermon was an act of public outreach.

So let us assume that this is the case, that as the procession led by the Verger orchestrated Donne’s return to the cathedral itself, he went with the sounds of the metrical Psalms in his ears. If they were the Psalms appointed for Morning Prayer on the 5th of November, they were Psalms 24, 25, and 26.

Making these Psalms part of the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project must await another grant, but in the meantime, if you would like the flavor of what they might have sounded like, go to this website.

Our final question is one of timing. We know that the typical Paul’s Cross sermon lasted about 2 hours, from roughly 10:00 in the morning to 12:00 noon. The time of the sermon was measured in two ways, by the passage of sand in an hour glass and by the ringing of the bell linked to the cathedral’s clock. This two-hour span started after the preacher delivered his opening prayer and declared his text.

But how long did the Paul’s Cross event last, from beginning to end? Already, we have seen that the prayer and the declaration of the text took place outside that two-hour window. In the recording at the heart of the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project, this part of the recording lasts about 8 and a half minutes. Ben Crystal’s performance of the sermon is slightly longer (in real time) than 2 hours, so perhaps we should regard the forematter as also being (in real time) a bit shorter, let us say 8 minutes.

The cathedral’s bell marking the quarter hours provides a good signal for beginnings, but allowing him only the seven minutes left between the 9:45 bell and the time he must start the Prayer before the sermon to get all that in before the 10:00 bell signals the beginning of his 2-hour window for the sermon itself.

So let us hypothesize that the bell marking the time at 9:30 served as a signal to begin the procession from the cathedral out to Paul’s Cross, which would have given the preacher generous time to make his procession and still arrive at the Cross in time to gather himself, make his way into the pulpit, take some preparatory breaths, and begin.

The Lord be with you!