Figure 1: Paul’s Cross, from about 75 feet. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

Figure 1: Paul’s Cross, from about 75 feet. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

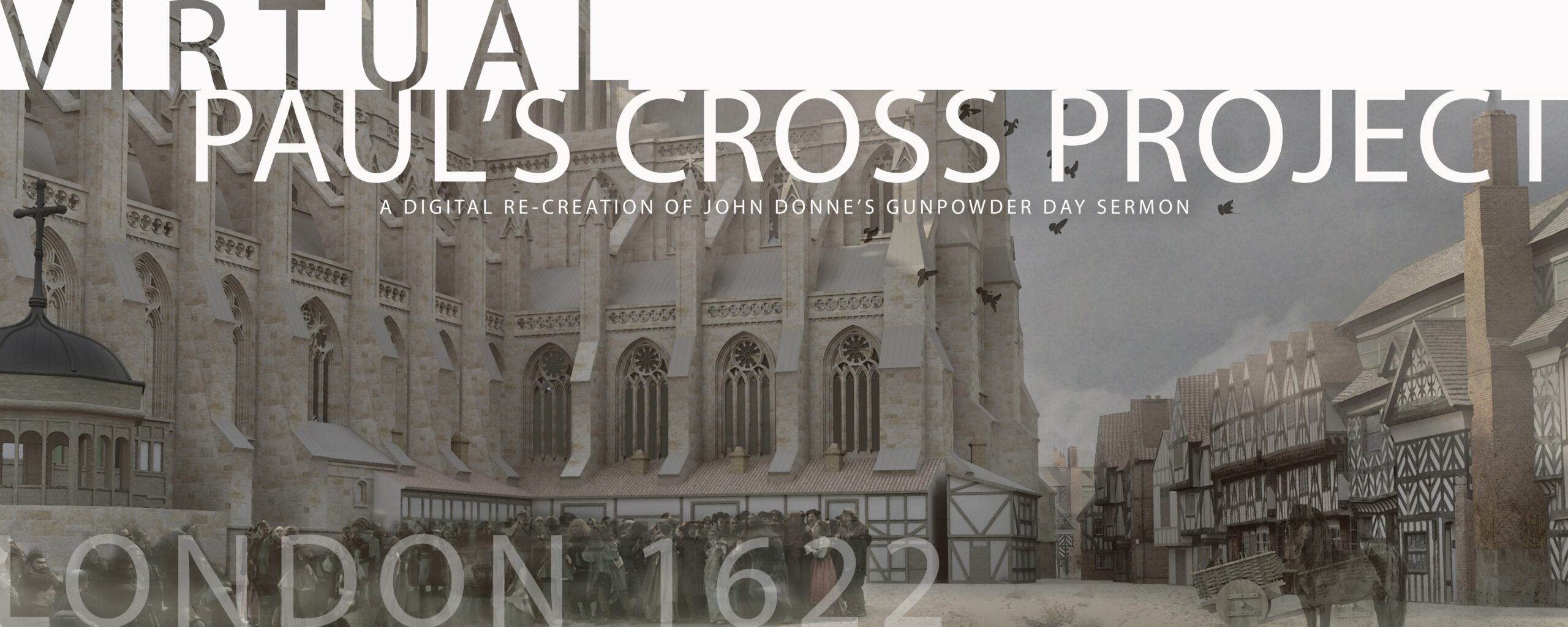

CONSTRUCTING THE VISUAL MODEL

The visual model depicts in detail the north-east corner of Paul’s Churchyard, including the Choir and North Transept of the Cathedral, the Paul’s Cross Preaching Station, and the buildings surrounding the Churchyard, chiefly mixed-use houses with retail book shops on the ground floor and living accommodations above.

The model also includes the buildings along the streets that run alongside the northeast corner of the Churchyard, specifically Paternoster Row to the north and The Old Change Street to the east, as well as their intersection at the west end of Cheapside Street.

The mixed-use buildings along the north and east sides of Paul’s Churchyard, as well as the structures that were built against the North Transept of the Cathedral, chiefly housed shops used by London’s booksellers to market their wares. The brick structure directly opposite the east end of St Paul’s is St Paul’s School, an institution founded by John Colet while he was Dean of St Paul’s (1505-1519) which later would support the education of generations of Englishmen, including John Milton.

Figure 2: St Paul’s Cathedral, Detail from the Copperplate Map (1550?). Image courtesy the Museum of London.

Figure 2: St Paul’s Cathedral, Detail from the Copperplate Map (1550?). Image courtesy the Museum of London.

PROCESS OF CONSTRUCTION

The Visual Model was constructed by Joshua Stephens, a graduate student in architecture at NC State University, using Google SketchUp. Images from the model were then modified in Photoshop by Jordan Grey, also a graduate student in architecture at NC State University, to incorporate details of the weather, climate, and environment of London in the early 17th century.

The visual model enables us to integrate evidence about the dimensions of buildings and spaces with evidence about their appearance. This evidence varies in specificity from detailed, recent archaeological measurement to visual images made in the 1500’s and 1600’s to recent images of similar or representative structures.

The discussion below describes the kinds of evidence we have used, and its relative degree of accuracy or extent of approximation.

Foundations of St Paul’s Cathedral

The most basic of these are the measurements of the foundations of the various structures in the Churchyard.

The foundations of pre-Fire St Paul’s Cathedral remain in the ground in London. They have recently been surveyed by John Schofield, Cathedral archaeologist, and published in his book St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (London 2011).

Our model of pre-Fire St Paul’s is grounded in these measurements.

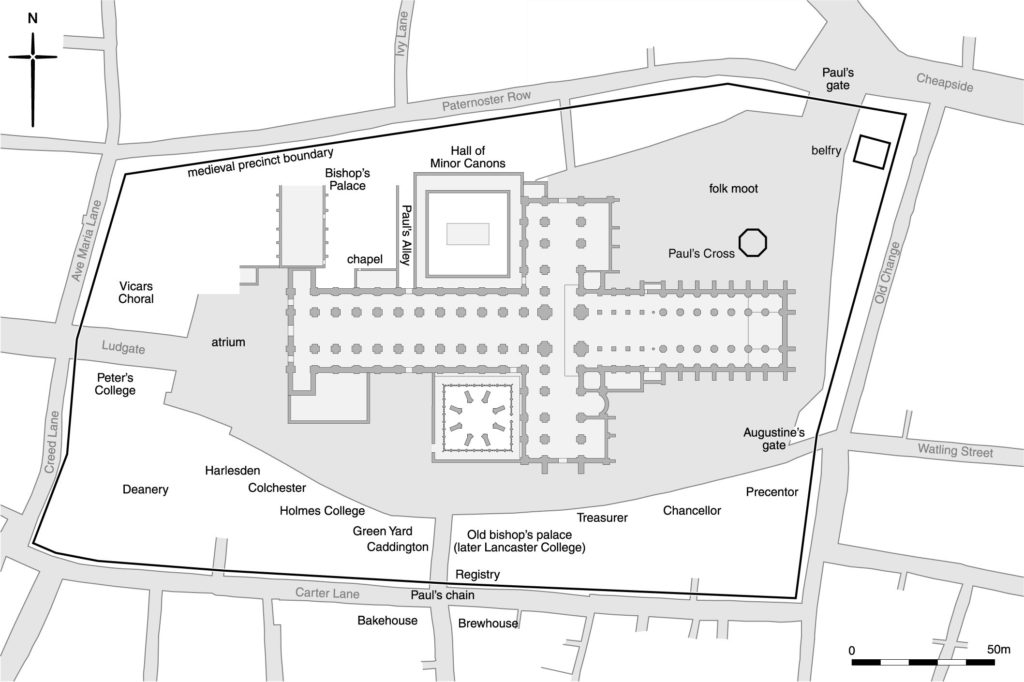

Figure 3: St. Paul’s Churchyard around 1450. Image courtesy John Schofield, from St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (2011).

Figure 3: St. Paul’s Churchyard around 1450. Image courtesy John Schofield, from St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (2011).

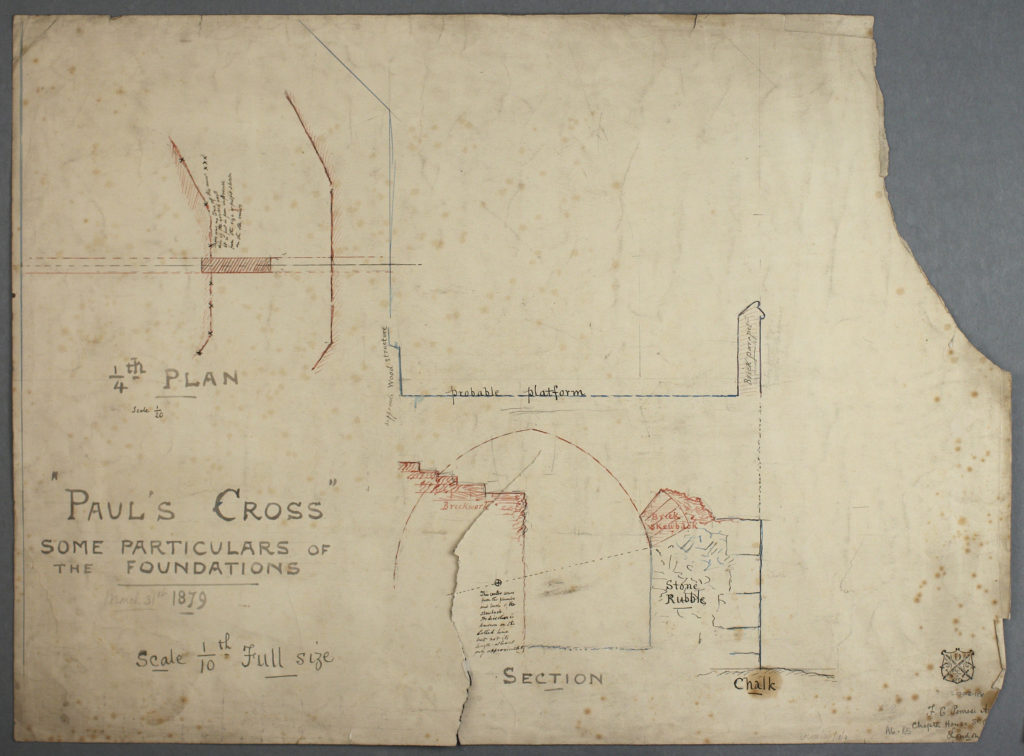

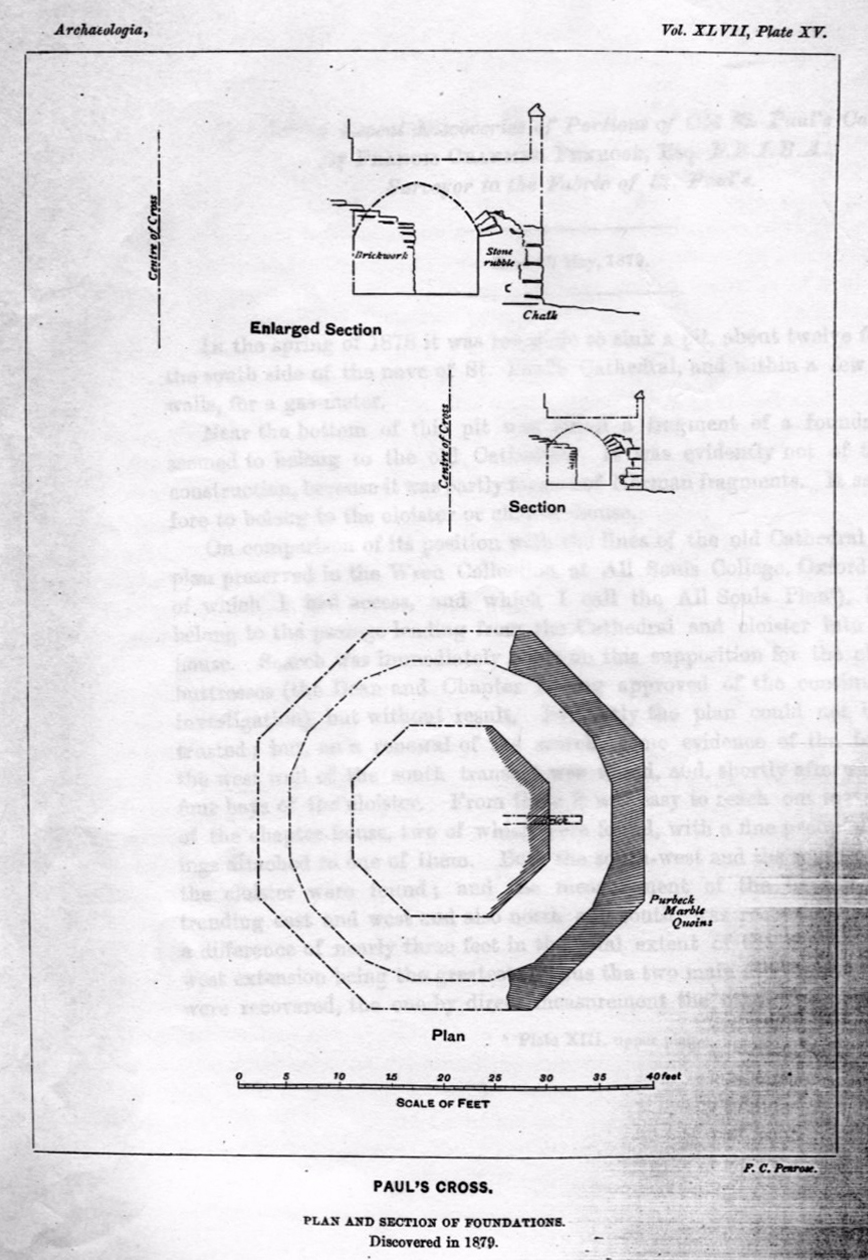

Foundations of Paul’s Cross

The foundation of the Paul’s Cross Preaching Station similarly remains in the ground in London. It was excavated and measured in 1878 by Francis Penrose.

Figure 4: Francis Penrose, Drawing of Paul’s Cross Excavation (1878). Image copyright the Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Figure 4: Francis Penrose, Drawing of Paul’s Cross Excavation (1878). Image copyright the Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Penrose published his findings in the journal Archaeologica in 1883. Our model of the Paul’s Cross Preaching Station is grounded in his measurements.

Figure 5: Scale Drawing of the Foundation of Paul’s Cross. From Penrose, “On the Recent Discoveries of Portions of Old St Paul’s Cathedral, Archaeologica 47 (1883), 381-92.

To read Penrose’s full account of his survey of the Paul’s Cross foundations, go here:

Foundations of Buildings in the Churchyard

The foundations of the buildings around the Churchyard were surveyed by the City of London after the Great Fire of 1666 destroyed the Cathedral and all its surrounding buildings. The results of these surveys have been gathered by Peter Blayney into his The Bookshops in Paul’s Cross Churchyard (London 1990). Our model of these structures is grounded in these surveys as reported by Blayney.

The dimensions of the buildings around the Churchyard are sometimes, though not invariably, indicated by the City of London surveyors whose records have been assembled by Blayney. They indicate that all these buildings were at least 3 stories high, while some were 4 stories high. We have followed their guidance in modeling the scale of these buildings.

Internal Measurements

The Cathedral

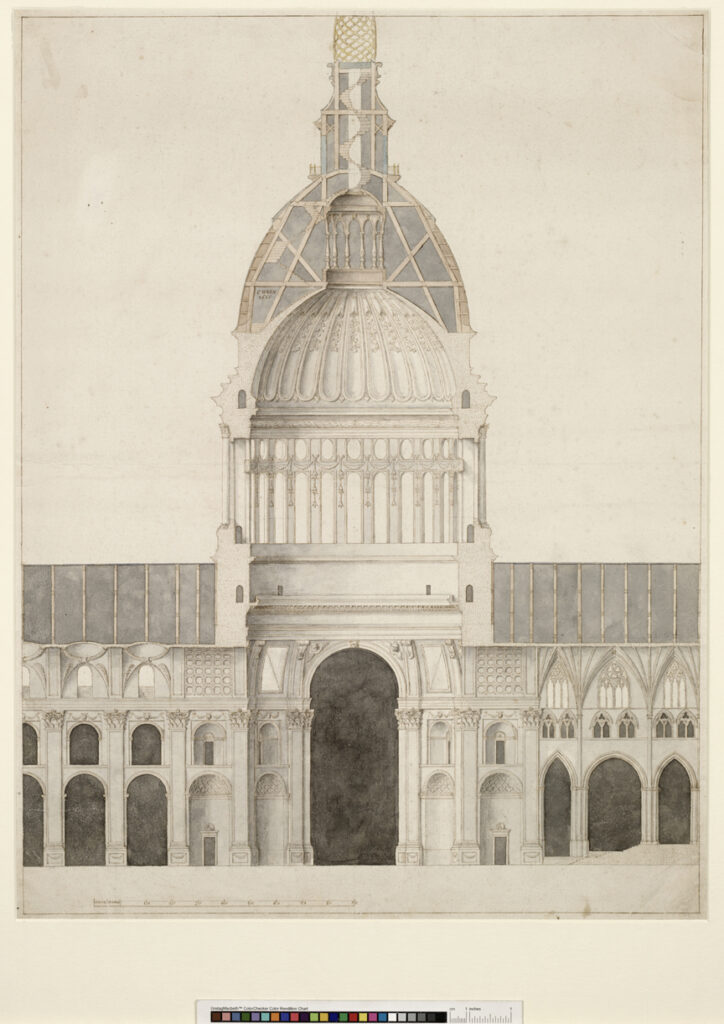

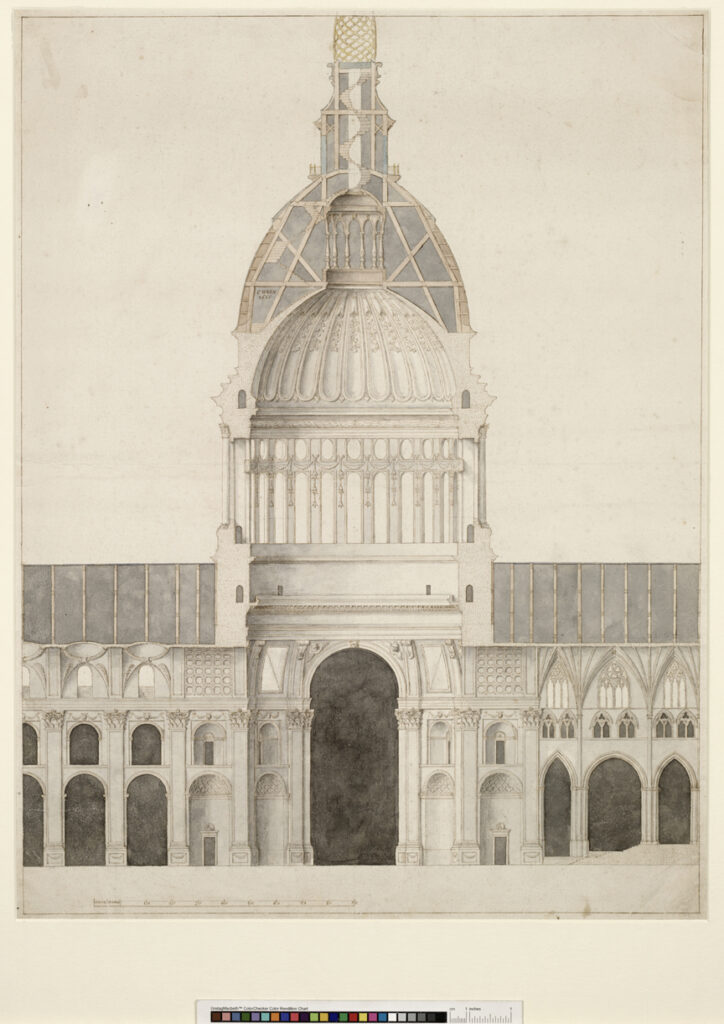

The internal dimensions of pre-Fire St Paul’s Cathedral were measured in the early 1660s by Christopher Wren, who had been hired by the Cathedral to devise a plan for renovation of the building. His measurements survive in a drawing he made showing the building with a neoclassical dome on top. Our model of the Cathedral incorporates his measurements.

Figure 6: Christopher Wren, Scale Drawing of pre-Fire St Paul’s Showing Proposed Dome (1662). Image courtesy Warden and Fellows, All Souls College, Oxford.

Paul’s Cross

There are no known measurements for the height of Paul’s Cross itself, though Penrose’s measurements of its base indicate that it was 17 feet across and rested on a foundation platform 34 feet across. Contemporary images of Paul’s Cross indicate that it was tall enough to stand inside comfortably and was large enough to accommodate several people. We have estimated the height of the Cross based on these considerations.

Figure 7: John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

Figure 7: John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

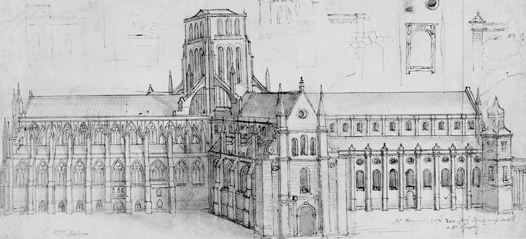

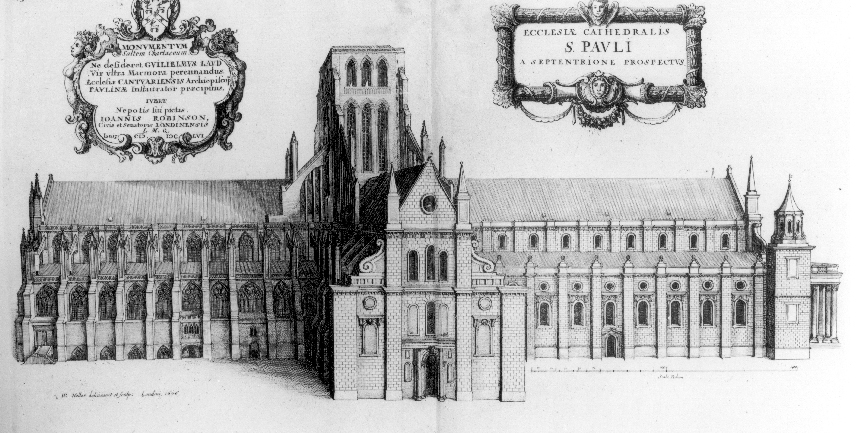

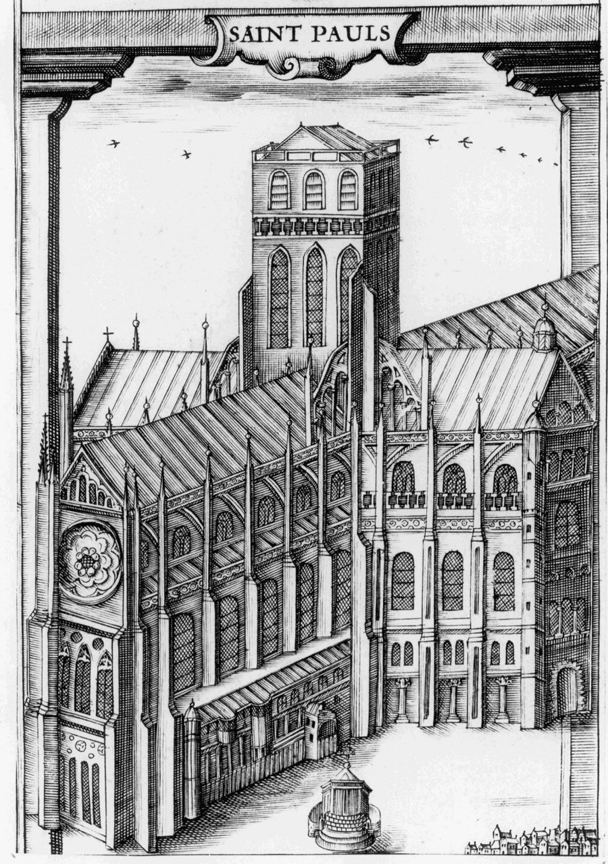

Appearance of St Paul’s Cathedral

Figure 8: Wenseslaus Hollar, Drawing, St Paul’s Cathedral, the east end (1650’s). Image courtesy of Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Figure 8: Wenseslaus Hollar, Drawing, St Paul’s Cathedral, the east end (1650’s). Image courtesy of Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

The appearance of pre-Fire St Paul’s is depicted in several contemporary sources, including 16th and 17th century maps of London, John Gipkin’s painting of the Paul’s Cross sermon (see image above)), engravings depicting the Paul’s Cross sermon, and, most especially, the engravings done by Wenseslaus Hollar for William Dugdale’s History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658), as well as two drawings of St Paul’s done by Hollar in preparation for his engravings.

Figure 9: Wenseslaus Hollar, drawing, St Paul’s Cathedral, north side (1650?). Image courtesy Sotheby’s, London.

Figure 9: Wenseslaus Hollar, drawing, St Paul’s Cathedral, north side (1650?). Image courtesy Sotheby’s, London.

None of these can be used without interpretation. The Gipkin painting, for example, truncates both the Choir and the North Transept of the cathedral, omitting from the image several bays of each structure.

Figure 10: Wenseslaus Hollar, engraving, St Paul’s Cathedral, north side. From William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Figure 10: Wenseslaus Hollar, engraving, St Paul’s Cathedral, north side. From William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

There are numerous images of pre-Fire St Paul’s and of the Churchyard produced during the centuries between the Great Fire and the present day. They are useless for our work, since they are dependent on the same images we have gathered for this project and cannot stand as independent witnesses to the appearance of the Cathedral or the Churchyard. They are at best companions in our common task of reimagining what this part of early modern London looked like.

The image of St Paul’s in our model is based on Hollar’s work, with the drawings given first priority, evaluated especially in light of Schofield’s archaeological research. The one exception here is the front of the North Transept, which in Hollar’s work shows the façade designed by Inigo Jones and built in the mid-1630’s. Here, we have evaluated images of the North Transept from Gipkin’s painting and engravings of the Churchyard to arrive at a design that is supported by the evidence and in keeping with the design of the rest of the building.

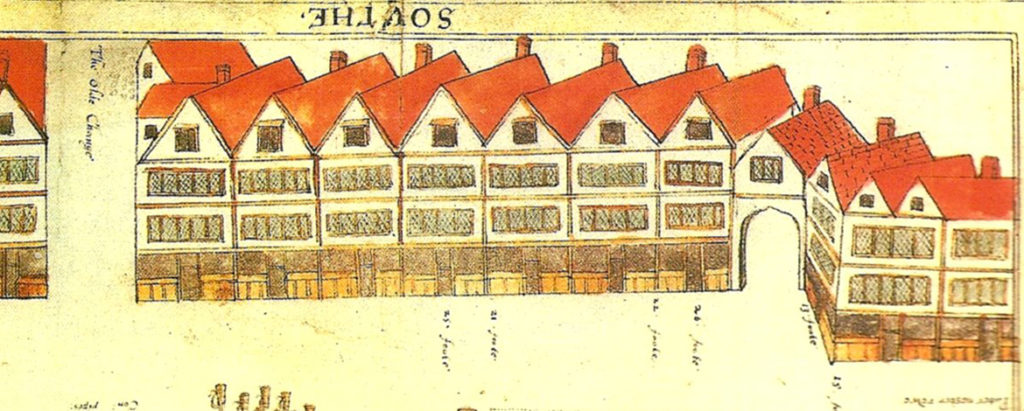

The Appearance of Buildings Surrounding Paul’s Churchyard

Regarding the buildings around the Churchyard, the best image is from a painting of the St Michael le Querne, at the intersection of Pater Noster Row and Cheapside (British Museum, BM Crace 1880-11-13-3516), but it shows houses facing outside the Churchyard. Other images that survive suggest stylized depictions rather than descriptive representations.

Figure 11: Drawing, London, Intersection of Pater Noster Row and Old Change (1585). British Museum ms. BM Crace 1880-11-13-3516. Image courtesy British Museum.

Figure 11: Drawing, London, Intersection of Pater Noster Row and Old Change (1585). British Museum ms. BM Crace 1880-11-13-3516. Image courtesy British Museum.

We have based all these structures on currently existing buildings from the Tudor/Stuart period that stand today either in cathedral towns or urban areas of England. Thus these structures constitute approximations of the original structures, definitely representative of what one would have seen there in the 1620’s, accurate models in the generic sense rather than the mimetic.

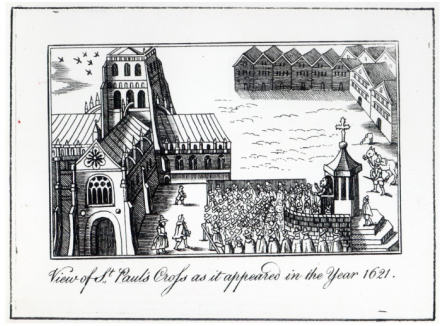

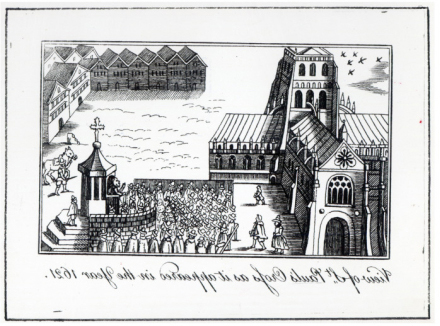

The Appearance of Paul’s Cross

Modeling Paul’s Cross itself has proved to be especially challenging. We know it was 17 feet wide at the bottom, large enough to accommodate several members of the preacher’s party, far enough above the ground to elevate the preacher above his congregation, with a roof high enough to be comfortably above the preacher’s head.

There are three independent contemporary images of the Cross, the Gipkin painting from 1616, an engraving in from 1611, and an engraving from the 1620’s that appears in at least 3 different versions.

Figure 12: Paul’s Cross. Detail, Map of Middlesex, from John Speed, The Theatre of Empire of Great Britain (1611). Image courtesy of the British Library.

Figure 12: Paul’s Cross. Detail, Map of Middlesex, from John Speed, The Theatre of Empire of Great Britain (1611). Image courtesy of the British Library.

Each of these images shows the building at a different scale, a different height, a different orientation. The images are, however, in general agreement about the shape of its roof.

Figure 13: Detail, John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

Figure 13: Detail, John Gipkin, Painting of Paul’s Cross (1616). Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London.

Each image has had to be evaluated, therefore, about what it can tell us about the design. For example, each image shows the Cross in a different orientation toward the Cathedral. The Gipkin painting shows it angled north-westward, toward the end of the North Transept. The 1611 engraving shows it angled toward the intersection of the Choir and the North Transept. The 1621 engraving shows it facing due west, toward the center of the North Transept.

Figure 14: View of St. Paul’s Cross as it appeared in the year 1621 (woodcut). Image courtesy Bridgeman Art Library.

Figure 14: View of St. Paul’s Cross as it appeared in the year 1621 (woodcut). Image courtesy Bridgeman Art Library.

Upon review, we decided that the Gipkin painting in effect “turned” the pulpit so that Gipkin could show the preacher’s face to the viewer. We think it unlikely that the preacher would face away from the Sermon House where the people of quality sat, so we concluded this orientation was a compositional rather than a representational detail.

We thought the 1611 image, with its orientation toward the Sermon House, had promise until we remembered that the Cross was built long before the Sermon House. Finally, we decided that the orientation due westward was the most likely and have adopted it in the model.

We considered how to resolve the conflict between the westward orientation of the Gipkin image and the 1611 image on the one hand, and the southward orientation of the 1621 image on the other until we realized that the 1621 image was actually a right/left reversal of the Gipkin image and settled on the westward orientation.

Figure 15: (Reversed) View of St. Paul’s Cross as it appeared in the year 1621 (woodcut). Image courtesy Bridgeman Art Library.

Figure 15: (Reversed) View of St. Paul’s Cross as it appeared in the year 1621 (woodcut). Image courtesy Bridgeman Art Library.

Our model thus shows St Paul’s Cathedral and the Churchyard as accurately as the evidence makes it possible to depict, with the range of approximation running from the highest with the buildings around the Churchyard (at best generically accurate depictions) to the lowest and most accurate with the Cathedral itself (under the guidance of archaeological evidence for size and location, Wren’s measurements for the dimensions, and Hollar’s images for the details of the design.

Figure 16: Paul’s Cross from 50 feet away. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

Figure 16: Paul’s Cross from 50 feet away. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

The Cross itself lies somewhere in between, a combination of a solid grounding in archaeological evidence plus more approximate depictions of the structure’s design and orientation, based on an interpretation of the representational evidence.

OUTWARD APPEARANCE

The color to use in depicting the Choir of St Paul’s has proven a challenge to identify.

Gipkin shows it to be a mustard-yellow color. We have instead chosen to show it a bit lighter than Gipkin.

The Choir of St Paul’s was built in the 13th century of Caen stone, as was the Tower of London from which we took the building’s color.

Figure 17: Tower of London. Image courtesy Wikipedia Commons.

Figure 17: Tower of London. Image courtesy Wikipedia Commons.

One reason depicting the building’s color has proved challenging is that yellow tones are highly susceptible to the changing character of light. Colors in the yellow family are highly susceptible to appearing darker and more saturated in the light of morning and afternoon (called the “golden hours” by photographers) when the light itself is more yellow than it is around midday or under an overcast sky when the light is more blue.