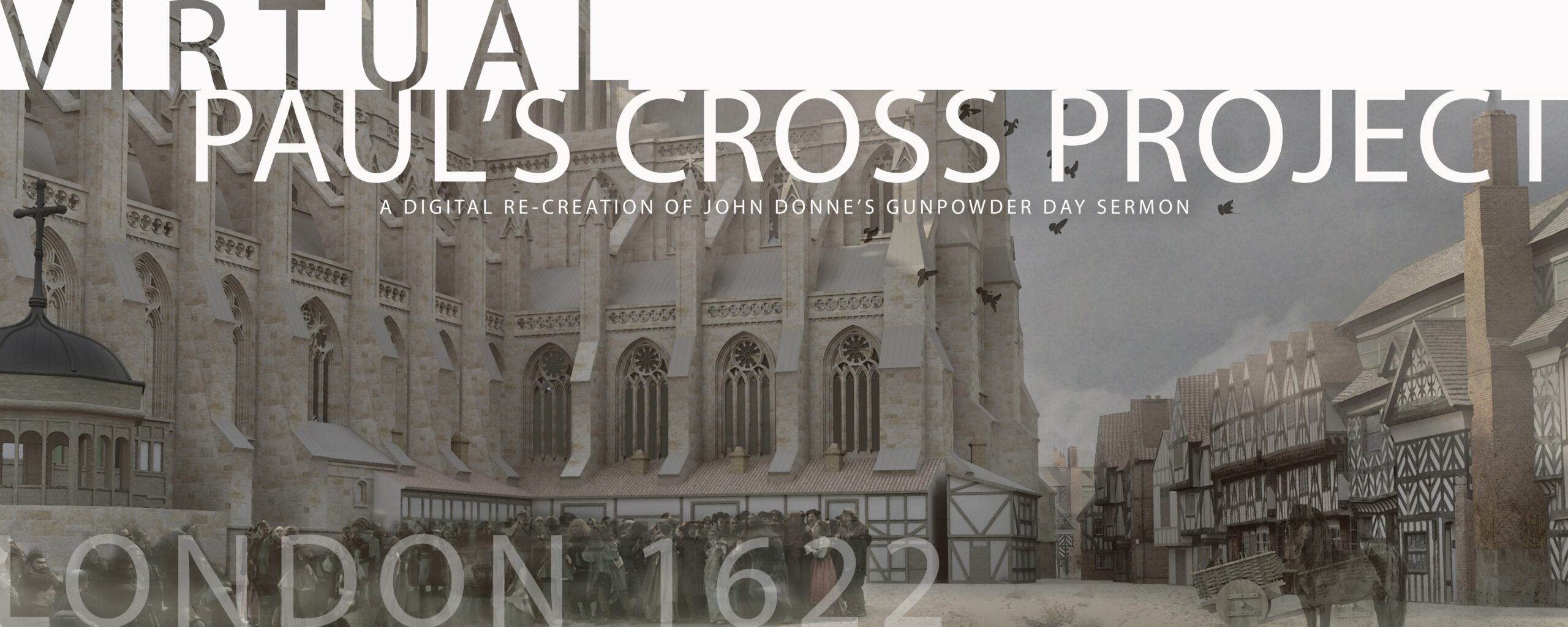

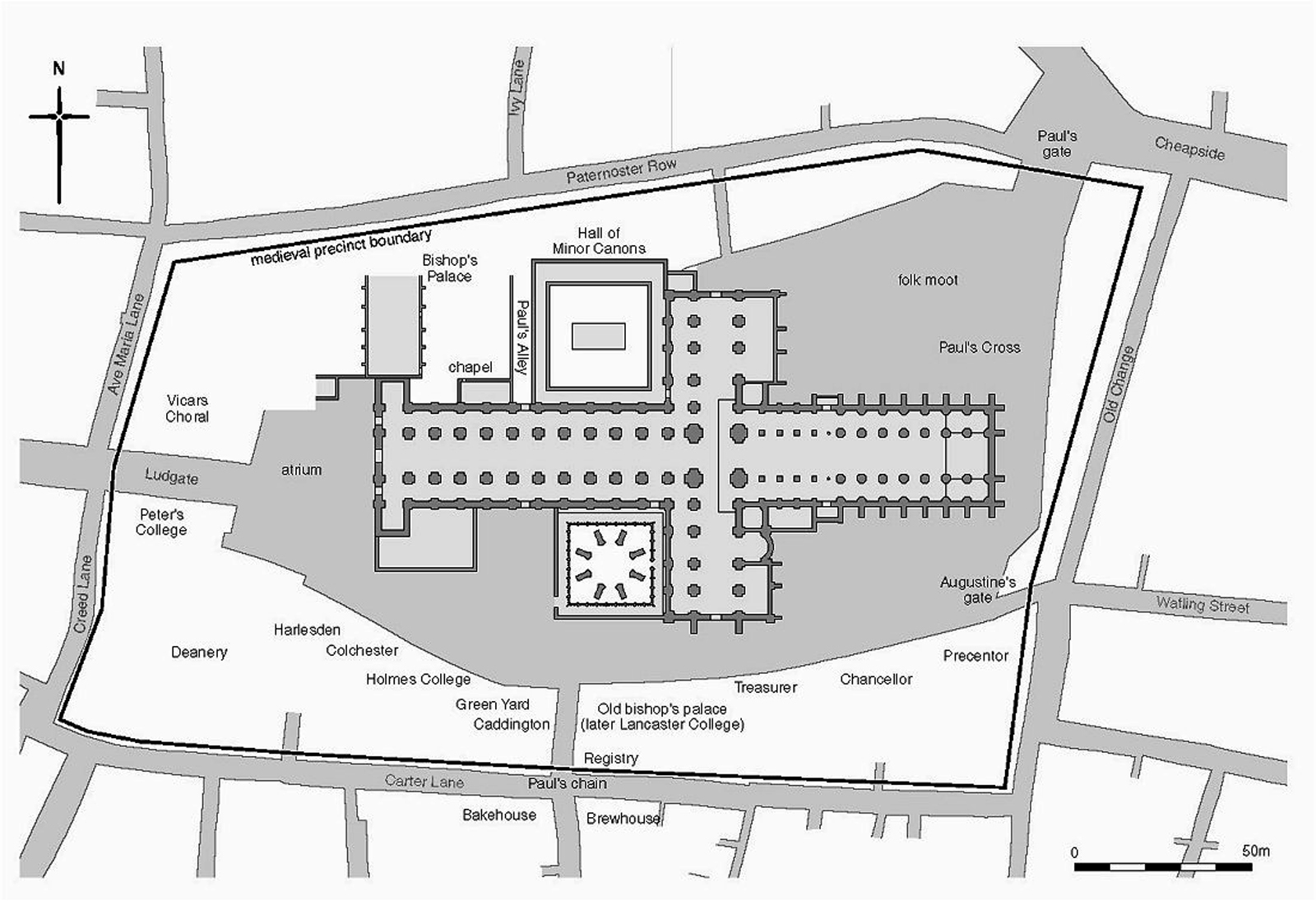

Figure 1: St. Paul’s Churchyard around 1450. Image courtesy John Schofield, from St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (2011).

THE PHYSICAL SPACE

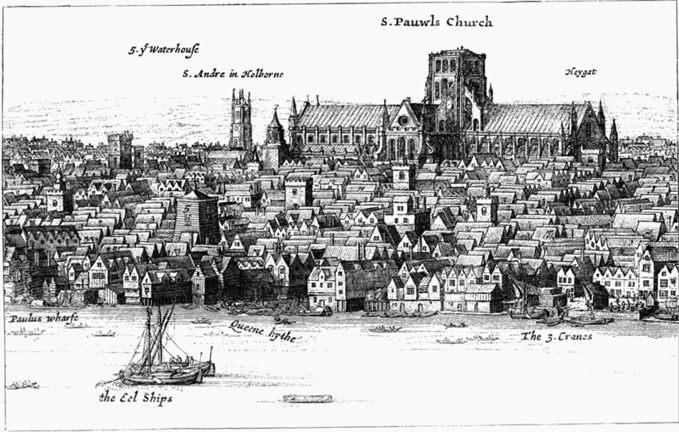

St Paul’s Cathedral sat on Ludgate Hill, one of the highest points in London in the early modern period. The cathedral as the most significant structure in the west of London in effect balances the Tower of London as the most significant structure to the east of London.

The scale of the cathedral’s construction meant that –even without its spire, which was destroyed by a fire ignited by lightning in 1561 — it rose above surrounding buildings and was a striking feature of the London skyline, especially as seen from the river.

Figure 2: Detail from Wenseslaus Hollar, engraving, London, Panoramic View, Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

The cathedral itself was surrounded by a wall that set Paul’s Churchyard apart from the rest of London. This boundary wall ran about 1800 feet west to east along Paternoster Row, about 1150 feet north to south along Old Change, about 1725 feet east to west along Paul’s Chain and Carter Lane, and about 825 feet from south to north along Creed Lane and Ave Maria Lane.

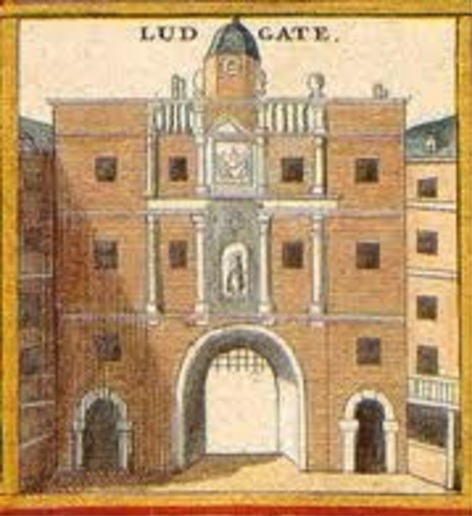

Figure 3: Ludgate from the West, circa 1650. Detail from contemporary woodcut. Image courtesy the Wikipedia Commons.

Access to Paul’s Churchyard was by means of 4 gates, Ludgate to the west, Paul’s Gate to the north, Augustine’s Gate to the east, and the gate at Paul’s Chain to the south.

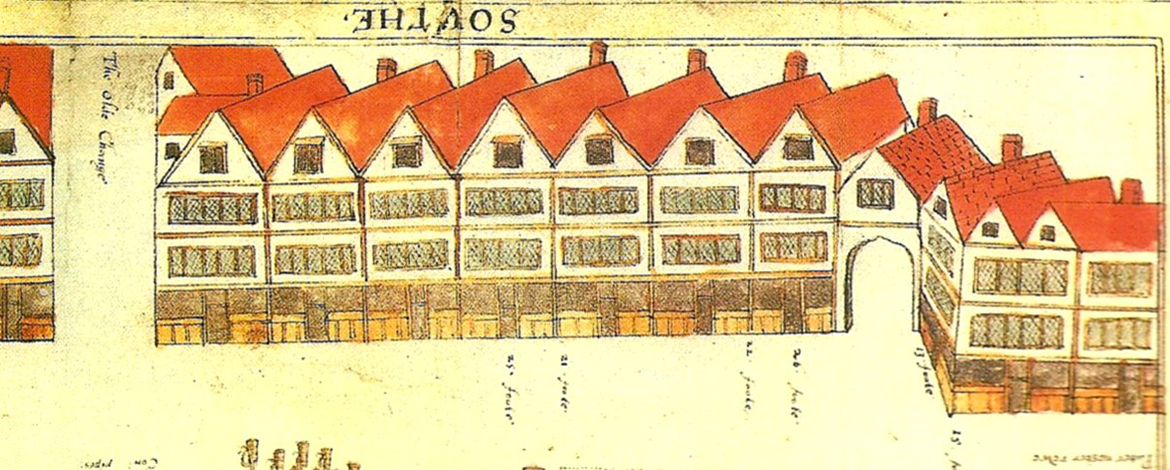

Figure 4: Drawing, London, Intersection of Pater Noster Row and Old Change (1585). British Museum ms. BM Crace 1880-11-13-3516. Image courtesy British Museum.

The image above, of Paul’s Gate from the north, shows us the buildings that defined Paul’s Churchyard to the north and east, but unfortunately from outside the Churchyard. The image below, from the Visual Model, puts us in a position to move through Paul’s Gate from the north and glimpse the cathedral within, as well as our first sight of Paul’s Cross.

Figure 5: Paul’s Gate from the North. Image from the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

The Built Environment

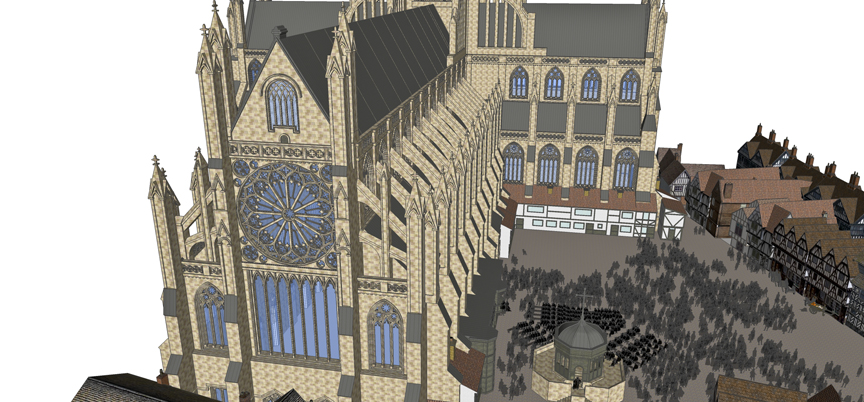

Within this space, St Paul’s Cathedral ran approximately 1150 feet from the great west door to the east end of the Choir with its grand rose window. It was approximately 175 feet across the transepts, from south to north. The nave and choir were each approximately 100 feet wide.

Figure 6: St Paul’s Cathedral and the Cross Yard, form the East. Image from the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens.

Access to the cathedral was chiefly from the west end, through Ludgate, although doors into the nave approximately half-way down the nave, and directly across from each other also gave access to the nave from both the north and south sides of the Churchyard. The presence of a walkway — Paul’s Alley — running north/south from the northern of these two doorways made it possible and easy to cut across Paul’s Churchyard from north to south by that route.

These points of access contributed to the nave of St Paul’s becoming a space unto itself, especially after the Reformation ended use of the nave for great processions and other festival liturgies. This space became Paul’s Walk, the place in London to see and be seen; this part of the cathedral was never used for worship services in the early modern period.

The Churchyard was lined with buildings to the south, including the Deanery where Donne lived and the homes of cathedral officials. Also just south of the Great West Portal was St Gregory’s Church, a parish church with its own congregation. To the west were other buildings housing cathedral officials, including lodging for the Vicars Choral, the adult members of the cathedral’s choir.

To the northwest was the Palace of the Bishop of London, George Montaigne when Donne became Dean in 1621, and William Laud in 1628. Here also was the Chapel of the Bishop of London, where Donne was ordained deacon and priest by Montaigne’s predecessor as Bishop of London, John King, in 1615.

The ground plan of Paul’s Churchyard at the top of this page shows a cloister between Paul’s Alley and the North Transept, but this was demolished after the Reformation, leaving a path around the north end of the North Transept leading to the north east section of Paul’s Churchyard where Paul’s Cross had stood since the end of the 14th century.

The passage through the nave from the great west door to the great north door, opening into the Cross Yard from the North Transept, provided a convenient shortcut from west London to the major intersection of the streets Cheapside and Old Change.

This area of the Churchyard had become the center of the English book trade during the 16th century, leading to construction of a series of buildings along the east wall of the North Transept and across the Churchyard from just off the North Transept around to Paul’s Gate and running south along the east side of the Churchyard to St Paul’s School which had been founded by John Colet in 1509.

Other buildings near Paul’s Cross included the Sermon House, built around 1569 to house People of Quality, including usually the Lord Mayor of London and his entourage. On at least one occasion in each of their reigns both Queen Elizabeth I and King James I attended sermons at Paul’s Cross, sitting in the Sermon House.

Figure 4: Memorial to Paul’s Cross, Paul’s Churchyard, St Paul’s Cathedral, London. Image courtesy John N. Wall, photographer.